I can hardly bare the Trungpa-Shambhala-speak everyone does at this point. Here's the last line of Dragon Thunder: "May all beings enjoy profound brilliant glory." What the hell does that mean?

Is that when you pump yourself up with tons of delusion? Like "I'm so great; my world is so great." People who think like this are headed for a big fall.

This world is a world of suffering, fools. There will NEVER BE "profound brilliant glory." Not even in your dreams.

The Way I See Trungpa Now

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

Regarding vegetarianism and the Buddha, Tibetan lamas always say, "We had to eat meat! That's all we had, and it was cold," etc. But we know there's more to it when they come to the West and they still eat meat. I was a vegetarian when I became a Buddhist back in 1975, and was a vegetarian until my lama told me, "Eat meat. It's good for you. And feed it to your kids." He said that when I had just been arguing with my husband that eating meat was not part of the Buddhist program. I was always trying to get around it. Sometimes he would confront me -- I cooked for him a lot -- and he'd say, "You're trying to not eat meat again, aren't you?"

I confess, I hated it, and meat never set well with me. Not ever. I started vomiting meat when I was 18, and I never ate beef after that. And as soon as I stopped "being" a Tibetan Buddhist -- like you could ever "be" anything but yourself -- I became a vegetarian again, and I am very glad for that.

I love Shabkar, and think he was the only real, true Tibetan lama. How can you love all sentient beings as your mother, and then eat them?

Trungpa never gave up eating meat. But then, I see very little compassion coming from him or anyone in his group. Shambhala people rarely, if ever, even say the word. They are way more concerned with decor than they are compassion.

I confess, I hated it, and meat never set well with me. Not ever. I started vomiting meat when I was 18, and I never ate beef after that. And as soon as I stopped "being" a Tibetan Buddhist -- like you could ever "be" anything but yourself -- I became a vegetarian again, and I am very glad for that.

I love Shabkar, and think he was the only real, true Tibetan lama. How can you love all sentient beings as your mother, and then eat them?

Trungpa never gave up eating meat. But then, I see very little compassion coming from him or anyone in his group. Shambhala people rarely, if ever, even say the word. They are way more concerned with decor than they are compassion.

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

But then, having people know that the world is a place of suffering, would not be good for business. Better to have people think the world is "Happy, happy, happy." Otherwise, people might say, "To hell with it all. It's all complete bullshit." And then they wouldn't play the game. Can't have people not playing the game. So Trungpa works for business.

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

These stories completely put the lie to Trungpa's enlightenment. Whatever enlightenment is supposed to look like, I'm just SURE it's not supposed to look like this:

Soon after the encampment ended, my doctor put me on bed rest because I was having some bleeding with my pregnancy. Rinpoche and I would hang out in bed together, and it was a very sweet, loving time for us. One evening, we had a small dinner at the Court to celebrate Mitchell's birthday. I was able to get up for this, but then I went back to bed and I watched The Exorcist on TV. Later I came downstairs to the kitchen to see Rinpoche. After we chatted for a while, Rinpoche went up the back stairs of the Court with his kusung, and I remained in the kitchen. He was in a playful mood, and he was jumping around on the stairs in a jaunty way. The kusung should have been behind him but was in front of him instead. Then I heard an incredible crash. I thought that somehow a chest of drawers had been pushed down the stairs. It turned out that Rinpoche had fallen and hit his head. When I found him at the bottom of the stairs, I became hysterical because he was briefly unconscious and I thought he was dead.

Mitchell was still at the Court, and he came immediately when he heard the crash. He came and examined Rinpoche, who was now awake and seemed fine -- much to our relief -- although upon examination, Mitchell found that he had a mild concussion. We decided to keep Rinpoche at home for the night. The next day, Rinpoche complained of a headache and said that, if he were anyone else, he "would have been licking ashtrays," referring to the intensity of the pain. Rinpoche's relationship to pain was quite different from most people's. Mitchell rushed him to the hospital at this point, where they found that he had bled into two small areas of his brain. He was allowed to come home, but he was confined to bed for a while.

We both had to stay in bed, and we started fighting. We had completely different sleeping and waking patterns, so we were constantly waking one another up. The whole atmosphere, which had been so sweet, was just awful. I now realize that Rinpoche was probably in a terrible mood because his head hurt. One night we had a horrible fight; we broke just about everything in the bedroom. I can't remember what it was about at all. I do remember both of us screaming and throwing things and breaking them. When the kusung came in, the whole room was in a shambles.

***

A few weeks after Ashoka was born, we received a letter from His Holiness the Karmapa saying that Ashoka was the incarnation of Khamnyon Rinpoche, the Mad Yogi of Kham, a very important Kagyu lama who had monasteries in both Tibet and India. We decided to wait and not to make any plans about Ashoka's future at that time. There was the question of Ashoka's parentage, and we didn't know what effect that might have in the future.

When we first brought Ashoka home from the hospital, I was staying with Rinpoche in our bedroom at Chateau Lake Louise. Rinpoche thought it would be nice if the baby was in bed with us, as we had done with Gesar. We tried this arrangement, but Rinpoche's kusung seemed to come into the room almost every half hour. Rinpoche was having stomach problems in that era, which continued for some time. He would get nauseous frequently, which was one reason that he would ring for a kusung to come in.

I on the other hand was experiencing some postpartum depression, or at least my hormones were raging and I felt vulnerable and exhausted. I desperately needed to rest at night. With people coming in all night long, and the baby waking up all the time, I finally freaked out completely and started screaming at Rinpoche. We had a huge fight. Rinpoche started screaming back at me and chased me around the bedroom until I finally barricaded myself in the bathroom with the baby. He thought I was being unreasonable.

***

... reminded me of a ride that I had taken with him in early 1984, shortly before I went to Germany for the last time. At that time, Rinpoche had been spending a lot of time in bed, and he seemed somewhat depressed, actually. Finally I said to him, "Come on. Let's get up and go for a drive somewhere." He wanted to take a drive up into the mountains, up Left Hand Canyon, north of Boulder. While we were out driving, I said to him, "You've got to cheer up." He was in a very black mood. I said again, "You've really got to cheer up." He didn't respond. So I said, "Come on, look out of the window. It's beautiful. It's a beautiful day. Look out. Remember, Shambhala Training, the Great Eastern Sun, and all of that." He just growled at me. So I said, "What's the matter with you?" He replied, "I'll be dead in three years." That certainly set me back. I said to him, jokingly, "You probably will, won't you, just to show me that you're right."

***

On the morning Rinpoche arrived at our home in Halifax, when the qualities game mercifully ended, I went upstairs to escape, but Rinpoche followed me. I encountered him in the upstairs hallway. He was standing with Osel, leaning on his arm. I said to him, "This situation is terrible. It's really awful. You are getting completely crazy. You are getting completely out of control, and you're killing yourself. You're drinking yourself to death." And he said, "Well, do you know what's the matter with you? You're a punk." (He was referring to my hairstyle; I had had my hair cut short and spiky in Germany.) I came right back at him. I said, "I may be a punk, but I'm not drunk." With that, he tried to hit me, but he missed.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

What difference does it make if you have a meeting in one place or another? Everything hinges on magic with these Shambhala people, who are NOT practicing Buddhism, but the ancient Bon religion of Tibet, to which Trungpa has more loyalty than to Buddhism BY FAR.

The difference, apparently, is in the POWER of the spot where Trungpa conducts his business. I suppose he has decided there are more dralas at the Court than anywhere else. And you know, those dralas are the ones who give you money and success, or don't.The wisdom of the Pon tradition was very profound, extremely profound....

The basic Pon philosophy is very powerful; it is much like the American Indian, Shinto, or Taoist approach to cosmic sanity. The whole thing is an extraordinarily sane approach. But there is a problem. It is also a very anthropocentric approach. The world is created for human beings....

The Pon tradition of Tibet was very solid and definite and sane....

Our Pon tradition is valid, because it believes in the sacredness of feeding life, bringing forth food from the earth in order to feed our offspring. These very simple things exist. This is religion, this is truth, as far as the Pon tradition is concerned....

For instance, we think the body is extremely important, because it maintains the mind. The mind feeds the body and the body feeds the mind. We feel it is important to keep this happening in a healthy manner for our benefit, and we have come to the conclusion that the easiest way to achieve this tremendous scheme of being healthy is to start with the less complicated side of it: feed the body. Then we can wait and see what happens with the mind. If we are less hungry, then we are more likely to be psychologically jolly, and then we may feel like looking into the teachings of depth psychology or other philosophies.

This is also the approach of the Pon tradition: Let us kill a yak; that will make us spiritually higher. Our bodies will be healthier, so our minds will be higher. American Indians would say, let us kill one buffalo. It is the same logic. It is very sensible. We could not say that it is insane at all. It is extremely sane, extremely realistic, very reasonable and logical....

Philosophies of this type are to be found not only among the Red Americans, but also among the Celts, the pre-Christian Scandinavians, and the Greeks and Romans. Such a philosophy can be found in the past of any nation that had a pre-Christian or pre-Buddhist religion, a religion of fertility or ecology -- such as that of the Jews, the Celts, the American Indians, whatever. That approach of venerating fertility and relating with the earth still goes on, and it is very powerful and very beautiful. I appreciate it very thoroughly, and I could become a follower of such a philosophy. In fact, I am one. I am a Ponist. I believe in Pon because I am Tibetan.

-- Crazy Wisdom, by Chogyam Trungpa

So much for the Tibetans getting away from "primitive beliefs about reality." Apparently, they just couldn't. There was too much "sanity" to it all.We find, in the next place, the doctrine of Elemental spirits. "When you shall be numbered among the Children of the philosophers," says the "Comte de Gabalis," "and when your eyes shall have been strengthened by the use of the most sacred medecine, you will learn that the Elements are inhabited by creatures of a singular perfection, from the knowledge of, and communication with, whom the sin of Adam has deprived his most wretched posterity. Yon vast space stretching between earth and Heaven has far nobler dwellers than the birds and the gnats; these wide seas hold other guests than the whales and the dolphins; the depths of the earth are not reserved for the moles alone; and that element of fire which is nobler than all the rest was not created to remain void and useless." According to Paracelsus, "the Elementals are not spirits, because they have flesh, blood, and bones; they live and propagate offspring; they eat and talk, act and sleep, &c.... They are beings occupying a place between men and spirits, resembling men and women in their organisation and form, and resembling spirits in the rapidity of their locomotion." They must not be confounded with the Elementaries which are the astral bodies of the dead. [2] They are divided into four classes. "The air is replete with an innumerable multitude of creatures, having human shapes, somewhat fierce in appearance, but docile in reality; great lovers of the sciences, subtle, serviceable to the Sages, and enemies of the foolish and ignorant. Their wives and daughters are beauties of the masculine type.... The seas and streams are inhabited even as the air; the ancient Sages gave the names of Undines or Nymphs to these Elementals. There are few males among them, and the women are very numerous, and of extreme beauty; the daughters of men cannot compare with them. The earth is filled by gnomes even to its centre, creatures of diminutive size, guardians of mines, treasures, and precious stones. They furnish the Children of the Sages with all the money they desire, and ask little for their services but the distinction of being commanded. The gnomides, their wives, are tiny, but very pleasing, and their apparel is exceedingly curious. As to the Salamanders, those fiery dwellers in the realm of flame, they serve the Philosophers, but do not eagerly seek their company, and their wives and daughters are seldom visible. They transcend all the others in beauty, for they are natives of a purer element."

-- The Real History of the Rosicrucians, by Arthur Edward Waite

And what can you say about this mixing together of psychotherapy jargon (they're all Freudian-Jungists) and paganism, but "Oy vey!"Sometimes he would go down to the office at Dorje Dzong. Other days, he would conduct business at the Court. As time went on, he spent more and more time at the Court and held many of his meetings there. He seemed in this era to be moving away from the corporate, office-based approach to business within Vajradhatu. Having seen the neurosis and limitations of that model, he began to make the Court the location for most meetings and the focus, or power spot, for decision making.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

In the "holy" business of recognizing tulkus, when a "high" lama recognizes a child as the incarnation of someone important, who cares who the parents are? In this case, as in many others, they didn't even need to see the child first, and give it tests. This proves that a lot more comes into this business than the "spirit" of the previous incarnation, like politics. Like if the politics are right, ANY CHILD can be recognized as a tulku. And with Trungpa, he was obviously considered a tulku factory.

Of course, it's all pretend.

In the West, we have an arms race. In Tibet, and among Tibetans today, they have a tulku race: who can recognize the most tulkus the fastest. People can even pretend to be tulkus in order to accomplish their money-making purpose.A few weeks after Ashoka was born, we received a letter from His Holiness the Karmapa saying that Ashoka was the incarnation of Khamnyon Rinpoche, the Mad Yogi of Kham, a very important Kagyu lama who had monasteries in both Tibet and India. We decided to wait and not to make any plans about Ashoka's future at that time. There was the question of Ashoka's parentage, and we didn't know what effect that might have in the future.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

Of course, it's all pretend.

During the 1980s, Thrangu made several visits to Taiwan, a Buddhist stronghold where interest in Tibetan teachers was growing as rapidly as this Asian Tiger's booming export economy. It was well known among Tibetan lamas that the best fund-raising was to be had in the overseas Chinese communities of East and Southeast Asia and North America.

"In 1984, Thrangu Rinpoche came up with an idea to get money in Taiwan," said Jigme Rinpoche, Shamar's brother, a lama in his own right and the director of two large monasteries in France since the mid-seventies. Like Shamar, Jigme lived at Rumtek in the sixties and seventies. Now in his late fifties, the soft-spoken, baby-faced Jigme exudes an air of motherly care that seems ill-suited to controversy; Yet, he has been the most outspoken of Shamar's supporters in criticizing Thrangu's role.

"Thrangu Rinpoche chose a monk, he was called Tendar," Jigme said. "He left Rumtek with Thrangu Rinpoche in 1975 and followed him to his retreat place Namo Buddha in Kathmandu. Thrangu Rinpoche had the idea to present this Tendar as a high lama."

With specific instructions from Thrangu, the new "Tendar Tulku Rinpoche" went to Taipei with the credentials of a spiritual master, in order to teach and raise funds for Thrangu's work in Nepal and elsewhere. Jigme told me that "Thrangu Rinpoche asked his own monks in Taiwan, who knew that Tendar was merely an ordinary monk, to keep his secret and pretend that Tendar was a high lama." The monks in Taiwan went along with Tendar's masquerade until the following year when Tendar himself, apparently fearful of discovery, backed out of the scheme, but not before raising enough money to demonstrate the potential of this approach to his boss Thrangu Rinpoche.

Thrangu later elaborated on this strategy and reportedly went on to promote dozens [over 24] of undistinguished lamas to rinpoches. "These lamas owed their new status and loyalty to Thrangu Rinpoche personally," Jigme explained. "Later, Situ Rinpoche followed his lead, recognizing more than two hundred [over 200] tulkus in just four months during 1991, as we learned from our contacts in Tibet."

In 1988, while traveling in Taiwan, Thrangu met with Chen Lu An. "Mr. Chen approached Thrangu Rinpoche with a plan to raise millions of dollars for the Karma Kagyu in Taiwan," explained Jigme Rinpoche. In exchange for a percentage of donations, a kind of sales commission that would go to his own Guomindang party, Chen offered to conduct a large-scale fund-raising campaign. Chen asked Thrangu to convey his proposal to the four high lamas of the Karma Kagyu: Shamar, Situ, Jamgon, and Gyaltsab Rinpoches.

Together, according to Jigme -- who said the Rumtek administration received reports from a dozen loyal monks in Taiwan who heard about this plan from their devotees and other Tibetans on the island -- Thrangu and Chen worked out the details of a plan to raise as much as one hundred million dollars by finding a Karmapa and then touring him around Taiwan.

Beforehand, they would create interest with a publicity campaign announcing the imminent arrival of a "Living Buddha" and promising that whoever had the chance to see the Karmapa and offer him donations would be enlightened in one lifetime. On his arrival, the tulku would perform the Black Crown ceremony at dozens of Tibetan Buddhist centers and other venues on the island.

"With such a plan," Jigme said, "according to our monks on Taiwan, Mr. Chen assured Thrangu Rinpoche that he would be able to get between fifty and a hundred people to donate one million dollars each, along with hundreds of others who would give smaller amounts."

Buddha's Not Smiling: Uncovering Corruption at the Heart of Tibetan Buddhism Today, by Erik D. Curren

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

Trungpa is really no better than any of these sleazy politicians who promise one thing -- so you vote for them -- and then give you something completely different after they are elected. I'm sure most of the people who started out with Trungpa were looking for something that looked like Tibetan Buddhism as they had heard of it, and was also in harmony with liberal American values of peace, harmony, justice, equality and democracy. Not that those two things go together, because they don't. But those are the values liberals held in that situation -- before they found out what Tibetan Buddhism was really all about -- and liberals for the most part were the ones coming to Trungpa. Of course, the monarchy idiots who came over from England are a whole 'nother story. That's where the trouble came from, from our age-old enemies the Tory English monarchists.

Boy, was he out of it! He thought he could get away with adopting a look that everyone in America has learned to hate.

I listened to some tapes the other day of David Rome being interviewed at The Chronicles, and PEOPLE ARE STILL TRYING TO FIGURE OUT what the hell a peaceful military is. Still hoping it has some validity and meaning for them, and that they weren't completely snookered during their years of following Trungpa.

But, as usual, the good people are tricked again and again by tricky Conservatives. That's what Trungpa was; a conservative, and no doubt about it. His idealized view of himself was to look like a petty third-world dictator (he couldn't hide who he really was).

Boy, was he out of it! He thought he could get away with adopting a look that everyone in America has learned to hate.

I listened to some tapes the other day of David Rome being interviewed at The Chronicles, and PEOPLE ARE STILL TRYING TO FIGURE OUT what the hell a peaceful military is. Still hoping it has some validity and meaning for them, and that they weren't completely snookered during their years of following Trungpa.

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

More proof that Trungpa was not enlightened is that he didn't know how to have a good party. Here, I am using an actual dream party as an example. I'm sure we all have dreams of being at wonderful parties, and I think dreams provide the best example of what a "pure" party is, and can be. I think that if you're enlightened, you should be able to throw a "pure" party.

First, there is a feeling of freedom at a good party. Everyone is free, and everyone is equal. There's no ideology restricting perceptions, like the ideology that the God-King is more important than everyone else, and everyone is there to please the God-King. There are no God-Kings at a good party. Hierarchies are inimical to a good party, because hierarchies take away equality, and without equality there is no freedom, and no free movement, so no goodness. At a good party, everyone is enlightened, everyone is high, and everyone experiences joy, love and awe at the spontaneous creativity that is going on. And everyone can connect freely with everyone else, and express their love to whoever wants to love them back.

As well, no restrictions apply to the expressions of art and creativity that go on at a good party, like that everything has to be "sacred" Tibetan art, or Steinerian restrictions that everything has to conform to the color blue, or Shambhalian restrictions that all art must be calligraphy, ikebana or archery. Creativity of any interesting nature can occur. Because people are free, their art is free. Art is not interesting unless it's new, and you've never seen it before, and it brings joy.

And, of course, at a good party love is happening everywhere. People aren't being stripped against their will, and coerced into having sex. You would want to flee from a party where that was occurring. A good party is a party where everyone is happy, and love is flowing unimpeded, and no one is getting hurt.

And lastly, the joy you feel at a good party comes from the positive nature of the party as a whole, and not from alcohol or drugs, which are artificial enjoyments. There's nothing artificial about real joy that comes from being free, from seeing amazing things, and experiencing love.

So, on all these counts, Trungpa gets an "F". He actually loses before the party even begins, because he insists on him being the focus of all attention. You can't have a good party with an egomaniac as your host. A good party host lets a party happen, and is never seen by anyone.

First, there is a feeling of freedom at a good party. Everyone is free, and everyone is equal. There's no ideology restricting perceptions, like the ideology that the God-King is more important than everyone else, and everyone is there to please the God-King. There are no God-Kings at a good party. Hierarchies are inimical to a good party, because hierarchies take away equality, and without equality there is no freedom, and no free movement, so no goodness. At a good party, everyone is enlightened, everyone is high, and everyone experiences joy, love and awe at the spontaneous creativity that is going on. And everyone can connect freely with everyone else, and express their love to whoever wants to love them back.

As well, no restrictions apply to the expressions of art and creativity that go on at a good party, like that everything has to be "sacred" Tibetan art, or Steinerian restrictions that everything has to conform to the color blue, or Shambhalian restrictions that all art must be calligraphy, ikebana or archery. Creativity of any interesting nature can occur. Because people are free, their art is free. Art is not interesting unless it's new, and you've never seen it before, and it brings joy.

And, of course, at a good party love is happening everywhere. People aren't being stripped against their will, and coerced into having sex. You would want to flee from a party where that was occurring. A good party is a party where everyone is happy, and love is flowing unimpeded, and no one is getting hurt.

And lastly, the joy you feel at a good party comes from the positive nature of the party as a whole, and not from alcohol or drugs, which are artificial enjoyments. There's nothing artificial about real joy that comes from being free, from seeing amazing things, and experiencing love.

So, on all these counts, Trungpa gets an "F". He actually loses before the party even begins, because he insists on him being the focus of all attention. You can't have a good party with an egomaniac as your host. A good party host lets a party happen, and is never seen by anyone.

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

I totally get it now! Tibetans are a primitive, wild, superstitious, crazy people who have deluded themselves into THINKING that they are Buddhists, so they can imagine that they have separated from their primitive past and are now modern people! Well, maybe "Buddhists" compared with these people, but they insist on keeping their blood-drinking, human-sacrificing visualizations to this day. And maybe "modern" 1,000 years ago.

They are a very cruel, suppressive people who pretend to realize compassion. Do compassionate people cut people's hands off for stealing? Do compassionate people live high on the hog in Lhasa while the majority of the population has barely enough to eat? Do compassionate people bang each other over the heads at religious celebrations? Do compassionate people try to scare the shit out of their population with the most horrible terroristic visualizations ever? Do compassionate people prevent their population from having any real medicines? Do compassionate people prevent their population from having any education? Do compassionate people prevent their population from even pursuing a craft? Do compassionate people prevent their population from playing sports? Do compassionate people tell everyone what to do at all times and in all situations, even when to wear winter clothes, and then summer clothes? This Tibetan story is a complete fraud.

And these people would completely OWN Buddhism as a whole! We absolutely cannot let this happen.

One of the monk policemen, bearing his heavy staff.

The Monks' Dance at the foot of the Potala, during the New Year's festivities.

And I have not been able to find ANY precedent for lamas having harems of wives. There is no doubt in my mind that if Trungpa had tried this in Tibet, he would have been sewn into a yak skin and thrown over a cliff.

But where is the ACTUAL civilization!?One night the droning of motors was heard over the Holy City and caused general alarm. Two days later news came from Samye that five Americans had landed there in parachutes. The Government invited them to come to Lhasa on their way back to India. The airmen must have been greatly astonished at being received in tents some way out of the city, and offered a hearty welcome with butter-tea and scarves. We were told in Lhasa that they had lost their bearings completely and that the wings of their plane had grazed the snow slopes of the Nyenchenthanglha. After this they had turned back, but finding that they had too little fuel to reach India they decided to scrap their plane and jump. Except for a sprained ankle or two and a broken arm they came down safely. After a short stay in Lhasa, they were convoyed by the Government to the Indian frontier, riding horses and as comfortable as one can be on trek in Tibet.

The crews of other American planes which came down in Tibet during the war were not so lucky. In Eastern Tibet the remains of two crashed planes were found; the members of the crews had all been killed. Another plane must have crashed south of the Himalayas in a province whose inhabitants are savage jungle folk. These people are not Buddhists, but naked savages reputed to use poisoned arrows. From time to time they come out of their forests to exchange skins and musk for salt and beads. On one of these occasions they offered objects which could only have come from an American aeroplane. Nothing more was ever heard of this disaster. I would have liked to go in search of the site of the accident, but the distance was too great.

-- Seven Years in Tibet, by Heinrich Harrer

They are a very cruel, suppressive people who pretend to realize compassion. Do compassionate people cut people's hands off for stealing? Do compassionate people live high on the hog in Lhasa while the majority of the population has barely enough to eat? Do compassionate people bang each other over the heads at religious celebrations? Do compassionate people try to scare the shit out of their population with the most horrible terroristic visualizations ever? Do compassionate people prevent their population from having any real medicines? Do compassionate people prevent their population from having any education? Do compassionate people prevent their population from even pursuing a craft? Do compassionate people prevent their population from playing sports? Do compassionate people tell everyone what to do at all times and in all situations, even when to wear winter clothes, and then summer clothes? This Tibetan story is a complete fraud.

Look at what they did to CIA agent Douglas Mackiernan as soon as he reached the Tibetan border. He had arranged a friendly reception, and this is what he got:The appearance of these various divinities is as follows: "In the middle of a vast wild sea of blood and fat, in the centre of a black storm rides on a kyang with a white spot on the forehead, which has a belt of raksasa heads and a raksasa skin as cover, with a crupper, bridle, and reins consisting of poisonous snakes, the dPal ldan dmag zor gyi rgyal mo remati, who comes forth from the syllable bhyo. She is of a dark-blue colour, has one face and two hands. Her right hand wields a club adorned with a thunderbolt, which she lifts above the heads of oath-breakers, the left hand holds in front of her breast the skull of a child born out of an incestuous union (nal thod) full of substances possessing magic virtues, and blood. Her mouth gapes widely open and she bares her four sharp teeth; she chews a corpse and laughs thunderously. Her three red and globular eyes move like lightning and her forehead is very angrily wrinkled. Her yellowish-brown hair stands on end, her eyebrows and the hair of her face bum fiercely like the fire ending a kalpa. Her right ear is decorated with a lion, the left one with a snake. Her brow is adorned with five human skulls, and she wears a garland of fifty freshly severed, blood-dripping heads. Her body is covered with splashes of blood, specks of fat, and is smeared with the ashes of cremated corpses. On the crown of her head shines the disc of the moon and on the navel the disc of the sun. She wears a scarf made of black silk and a human skin serves her as a Covering; her upper garment is made of rough black cloth and her loin-cloth is the freshly-drawn skin of a tiger, fastened by a girdle consisting of two entwined snakes. From the saddle-straps in front is suspended a sack full of diseases, from the straps in the back a magic ball of thread. A khram shing is stuck into her waist-belt. A load of red tablets and a pair of dice, white and black, hang from the straps. On her head she wears an umbrella of peacock-feathers.

In the back of the chief goddess comes forth from the white syllable bhyo, on top of a white mule adorned with a precious saddle and bridle, the Zhi ba'i Iha mo, of a white colour, with one face and two hands, peaceful and smiling - though in a slightly angry mood - and possessing three eyes. Her azure-blue hair hangs down and its locks are bound together with a golden thread into a single tuft. Her right hand holds a white mirror of silver showing clearly the happenings in the visible world, her left hand holds a white vessel of silver with a six-pointed handle filled with various medicines. She carries a diadem, earrings, a necklace, the se mo do ornament, a garland, and a girdle, and her hands and feet are adorned with bracelets, all these objects having been made of jewels. She wears a flowing dress consisting of white silk, blue 'jag and yellow sha dar, bound together by a sash of blue silk. She sits with her legs half crossed. A yellow ray emanates from her body (out of which originates) the train which surrounds her, carrying out (the kind of work called) zhi ba'i las.

To the right side of the chief goddess comes forth from the yellow syllable bhyo, on top of a yellow mule adorned with a precious saddle and bridle, the yellow rGyas pa'i lha mo with one face and two hands, bearing the expression of passion. She has three eyes, her azure-blue hair is bound by means of a golden thread into a tuft slanting to the left. Her right hand holds a golden vessel full of amrta and her left hand holds a golden pan full of wish-granting jewels. She carries a diadem, earrings, a necklace, the se mo do ornament, a garland, and a girdle, and her hands and feet are adorned with bracelets, all these objects having been made of jewels. She wears a dress made of yellow silk, blue 'jag and sha dar rgya khas, bound together by a sash of blue silk. She sits with her legs half crossed. A yellow ray emanates from her body (out of which originates) the train which surrounds her, carrying out the (work called) rgyas pa'i las.

To the left of the chief goddess comes forth from the red syllable bhyo, on top of a red mule adorned with a precious saddle and bridle, the red dBang gl lha mo with one face, two hands, assuming within a moment's time a fierce and passionate expression; she has three eyes. Her azure-blue hair is bound by means of a golden string into a tuft slanting towards the left. Her right hand thrusts a hook and the left one a snare. She carries a diadem, earrings, a necklace, the se mo do ornament, a garland, and a girdle, and her hands and feet are adorned with bracelets, all these objects having been made of jewels. She wears a flowing dress made of red silk, green 'jag and blue sha dar, bound together by a sash of green silk. She sits with her legs half crossed. From her body emanates a ray of red light (out of which originates) the train which surrounds her. carrying out the (work called) dbang gi las.

In front of the chief goddess comes forth from the dark blue syllable bhyo, on top of a black mule covered by a skin which had been drawn from a corpse, the black Drag po'i lha mo, with one face and two hands, staring with three widely opened eyes, wrathful and ferocious, with a gaping mouth and baring her long teeth; the eyebrows and the hair of her face blaze like fire and her dark-brown hair is similar (to the colour of) the dusk. She has flapping breasts, her right hand holds a khram shing and the left hand (carries) a stick consisting of a mummified corpse, together with a Snare. Atop of a garment made of coarse black cloth she wears a fluttering cover made of a human skin and (she also carries) a loin-cloth made from the skin of a tiger. She is adorned with five kinds of bone ornaments. She has the attitude of a rider. A black ray emanates from her body (out of which originates) the train which surrounds her, carrying out the (work called) drag po'i las.

In front of the Drag po'i lha mo comes forth from the dark-blue syllable bhyo - when all has been completely changed -, on top of a huge corpse lying on its back, the Iha mo remati gsang sgrub; she has one face, two hands, and is very angry and ferocious. Her three red eyes are globular, her eyebrows and the hair of her face are ablaze, and her darkbrown hair hangs in streaks down to her heels. Her brow is adorned with a diadem bearing one skull. She is naked (except for) a pair of trousers made of coarse cloth. Her right hand lifts skyward a sharp strong sword, her left hand holds by the hair, towards her left breast, a blood-dripping human head. She dwells in the centre of a fire, in the manner of rising hesitantly.

In front appears from the syllable ma the black Srog bdud ma, with two hands, crushing the sun and the moon, riding on a black bird. On the left comes forth from the syllable ma the black sNying bzan ma. She eats the human heart which her right hand is holding, her left hand (clutches) a hook; she is dressed in trousers of blue silk and (dwelling) on top of a corpse she assumes a running posture. In the back comes forth from the syllable ma the fierce red-brown Thog 'phen ma, with two hands, holding a sack full of lightning and hail, which she pours out on the enemies. Standing on the sun with her right foot and on the moon with the left one, she hastens on the sky. Each of these three has the mouth widely open and bares the teeth. Their three eyes move like lightning, the eyebrows and the hair of the face are blazing. Their hair hangs down reaching to the thighs, and their brow is adorned with three dry skulls. On the left comes forth from the syllable ma the black scorpion-headed Nad gtong ma. Her right hand is open, the left One holds a sack full of diseases. She rides on a camel. - Each of these four has flapping breasts and a garland of poisonous snakes. In addition to it Nad gtong ma opens widely her genitals.

In the southeastern direction comes forth from the syllable Ta the dark-brown Khyab 'jug. chen po with nine heads, the three on the right being white, the three on the left being red, and the three middle-ones being dark-brown. Atop of these faces he has the head of a raven; his yellow-red hair stands on end, his eyes are widely open, and he bares his teeth. His first pair of hands holds an arrow and a bow in the attitude of shooting, the lower pair holds a victory-banner with the head of a makara as its point (chu sTin gyi Tgyal rntshan) and a snake forming a noose. The lower part of his body is the green coiled tail of a snake, his body is covered with a thousand eyes and he has a face on his belly. He is adorned with a diadem of skulls, a human skin (which serves him) as an upper cover and with jewels, bone ornaments, and snakes.

In the southwest comes forth from the syllable tsa the red three-eyed bTsan rgod. His upper teeth, gnawing the lower lip, gnash in anger. His right hand thrusts a lance and the left one a snare. He wears a cuirass and a helmet (both made) of leather and on his feet he wears high red boots. He rushes away on the "red horse of the btsan" adorned with a saddle and crupper.

In the northwest appears from the syllable du the lion-faced black bDud mgon whose locks of turquoise stand on end. His right hand lifts a lance and the left hand throws a dmar gtor at the enemies. He wears a garment with a train, of red 'jag and black silk, and he is decorated with the six kinds of bone-ornaments. He rides on a black horse bearing a saddle and a crupper.

In the northeast comes forth from the syllable Isa the rgyal po Li byin ha ra, of a pink lustrous hue, in a peaceful, not angry disposition, with three eyes. His yellow-red hair is turned upward and he wears the (hat called) sag zhu. His right hand lifts a thunderbolt and the left one holds a skull-cup in front of the breast. He carries atop of a patched-up cloak a red robe with a train, having a blue mtha' 'jag. He wears Mongolian boots (Hor lham) with three soles atop of each other, and he rides in the raja-paryanka on an elephant with a long trunk.

From the syllable bhyo comes forth in front of the mule (of the chief goddess) the dark-blue Chu srin gdong can, holding a snare in the right hand and the reins (of the mule) in the left one. She wears a human skin as her dress. Behind (the mule) is the dark-red Seng ge'i gdong can holding a chopper and a skull-cup full of blood. In the four directions (as seen from the chief goddess) appear: in front the dark blue bDud mo remati holding a sword in her right hand and a skull-cup full of blood in the left one. She is dressed in a human skin and a garment of black silk and rides on an ass with a white patch on its forehead. On the right side is the dark-blue Nad kyi bdag mo holding a pair of dice in her right hand and a red tablet in the left one. She is dressed in a garment made of black silk and a rough cloth; she rides on a mule. In the back is the black sKye mthing ma, holding a human heart in her right hand and making with the left hand the tarjani-mudrii. She is dressed in a human skin and in the skin of a tiger, and she rides on a stag. On the left is the white Khri sman sa le ma, lifting skyward with both her hands the skin of a makara. She wears a dress and a turban of white silk, and rides on a black bird.

In front, in the right corner originates from the syllable bhyo the dark-blue dPyid kyi rgyal mo, "the 'queen of spring", holding a chopper in her right hand and a skull-cup full of blood in the left. She is dressed in a human skin and rides on a mule. In the back, in the right corner, originates from the syllable bhyo the dark-red dByar gyi rgyal mo, "the queen of summer", holding a hook in her right hand and a skull-cup full of blood in the left one. She is dressed in (silks of the kind called) chu dar and she rides on a water-buffalo. In the back, in the left corner, comes forth from the syllable bhyo the yellow sTon gyi rgyal mo, "the queen of autumn", holding a sickle in the right hand and a skull-cup full of blood in the left one. She wears a cloak of peacock feathers and rides on a stag. In front, in the left corner, appears from the syllable bhyo the dark-blue dGun gyi rgyal mo, "the queen of winter", holding a magic notched stick in her right hand and a skull-cup full of blood in the left one. She rides on a camel which has a white spot on the forehead.

In front appears from the syllable mam the white bKra shis tshe ring ma, holding a thunderbolt and a bum pa and riding on a lion. From the syllable mam originates the azure-blue mThing gi zhal bzang ma, holding a ba dan and a mirror and riding on a kyang. From the syllable mam comes forth the yellow Mi g.yo blo bzang ma, holding a pan with food and an ichneumon. She rides on a tiger. From the syllable mam comes forth the red Cod pan mgrin bzang ma, holding a jewel and a treasure box. She rides on a stag. From the syllable mam comes forth the green gTad dkar 'gro bzang ma, holding a bushle of durva grass and a snare. She rides on a dragon. Each of these five bears an angry, passionate, haughty expression. They are adorned with dresses of silk and ornaments of precious stones.

On the left originates from the syllable ma the blue rDo rje kun grags ma, wearing a cloak of a thousand black snakes and having the freshly drawn skin of a yak as her loin-cloth. She holds a phur bu (of the kind called bya rgod phur bu). She rides on a turquoise (coloured) dragon. From the syllable ma comes forth the blue rDo rje g.yd ma skyong, wearing a freshly drawn yak-skin as her dress and a loin-cloth of a thousand khyung-wings. She holds a phur bu of copper (and) rides on a three-legged mule. From the syllable me originates the white rDo rje kun bzang ma, wearing a lion skin as covering. She lifts a five-pointed thunderbolt and rides on a lion. From the syllable me originates the blue rDo rje bgegs kyi gtso, wearing a dress made from a thousand black bulls and a loin-cloth consisting of a thousand khyung wings. She holds an iron phur bu and rides a golden-coloured hind.

In the back comes forth from the syllable la the white rDo rje spyan gcig ma, wearing a dress spun of conch-shells, tied together by a girdle of turquoise. She holds a "blood-sack" (khrag gi rkyal pal and rides on a white "conch-shell stag". From the syllable la comes forth the yellow rDo rje dpal gyi yum, dressed in a human skin, with a loin-cloth of human hearts, holding a poisoned arrow with a black notch and riding on a khyung. From the syllable Ie originates the white rDo rie klu mo, wearing a cloak of piled-up human heads and holding a club consisting of a corpse. She rides a black wild boar. From the syllable le comes forth the green rDo rje drag mo rgyal, (wearing) a rlog pa consisting of a thousand yak-skins and a loin-cloth made of a thousand khyung wings. She holds a phur bu (of the kind called mchog phur) and she rides On a wild yak with nine horns.

On the left comes forth from the syllable ta the black rDo rje dpal mo che, with a klog pa of a thousand lion-skins and a loin-cloth full of black snakes. She holds a bum pa with blood in it and rides a white horse. From the syllable ta comes forth the red rDo rje sman gcig ma, with a covering of a thousand (skins drawn from) white horses of the best breed and a loin-cloth consisting of a thousand tiger-skins; she holds a phur bu (of the kind called 'bse'i phur) and rides on a black mule with a yellow muzzle. From the syllable te comes forth the dark-red rDo rje g.ya' mo sil, wearing a covering full of black snakes. She holds a phur bu made of sandal-wood and rides on a hind. From the syllable te comes forth the blue rDo rje dril bu gzugs legs ma, having a covering of a wolf (skin) and a loin-cloth of human ribs (and) fibres. She holds a small drum and a thighbone trumpet and she rides on a lion of turquoise.

In the main train of these appear towards the outside the ma mo, bdud, gshin rje, srin po, zhing skyong, etc., in an unimaginable multitude, and moreover the lha, klu, gnod sbyin, dri za, grul bum, mi 'am ci, Ito 'phye chen po, etc., in an unimaginable multitude, brandishing in their right hands various weapons as thunderbolts, choppers, swords, hatchets, lances, hooks, iron poles to empale criminals, fiercely blazing fire, etc., while all of them hold in the left hand a skull-cup full of poisonous blood."

-- Oracles and Demons of Tibet: The Cult and Iconography of the Tibetan Protective Deities, by Rene De Nebesky-Wojkowitz

This is the explanation for Chogyam Trungpa strutting around in his uniform, pinning medals on himself, and looting Americans. That's what Tibetan men do: kill, loot and suppress. Generosity to a Tibetan is to share a bite of his victim.

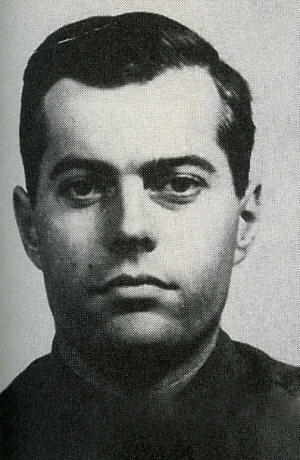

Passport photo of Douglas S. Mackiernan, then working for the CIA undercover as a State Department employee. While others shunned assignment to China's remote far west, he was only too eager to set up a listening post there along the Sino-Soviet border. (Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

For Mackiernan two more months would pass at the frozen campsite. Finally, on March 20, 1950, he and his band said good-bye to the Kazakhs and commenced the final and most grueling leg of their journey, over the Himalayas, into Tibet, and eventually to India. From here on, Mackiernan and his men would be ever more exposed to the elements. At night, Mackiernan would lie down in his sleeping bag, huddled against the back of a camel to shield him from the wind. At morning he and Bessac, the two Americans, could no longer assist in saddling the camels. Their fingers were too numb.

Mackiernan and his party would take turns riding the camels and then walking. Too much riding and they could freeze to death. Too much walking and they would collapse from exhaustion. Their diet, too, required a delicate balance. From the White Russians, more seasoned in the ways of survival, Mackiernan learned what to eat and what not to eat. Too much meat at such an altitude and he could find himself wooed into a nap from which he would not awake. Instead, he nibbled on bits of sugar, rice, raisins, a few bites of meat, and the ever-present biscuits he kept in his pants pocket.

It was all a matter of balance upon which his survival depended. At elevations of sixteen thousand feet or more, the air was so thin that the already taciturn Mackiernan rarely spoke at all, trying to conserve his breath. All conversation ended. In its place were hand signals and one or two-word directives: "brush" or "dung" for fires, "snow" to be melted for water. By now, the ordeal of marching had become a mindless and silent routine, one foot in front of the other. Some days Mackiernan would lose sight in one eye or the other, the result of transient snow blindness.

Many of the horses had died from starvation. Others were useless, their hooves worn out. Knowing that the rest of the way there would be little grass to eat, Mackiernan had long before bartered for camels -- not just any camels, but those that ate raw meat. Before making the purchase he tied up his prospective purchases and waited a day to see which camels consumed meat and which were dependent upon a diet of grass. Those camels that resisted meat Mackiernan promptly returned. Where he was bound, there would be no easy forage.

Though there was an abundance of game -- wild horses, sheep, and yak -- the elevation presented its own unique problems of consumption. At sixteen thousand feet, Mackiernan found that water boiled at a decidedly lesser temperature. He could thrust his hand up to the elbow in furiously boiling water and remove it without a hint of scalding. One day Mackiernan shot a yak. The men salivated over the prospect of yak steaks. But after four hours in the boiling cauldron, the meat was still raw.

There were other problems too. A wild horse was spotted on a distant ridge and was brought down with a single shot. But almost instantly, vultures appeared overhead. By the time the men reached the animal, its carcass was nearly picked clean, its ribs rising out of the snow. After that, Mackiernan and his men shot only what they could reach quickly, then concealed their kill beneath a mound of grasses and stones until they had taken what they needed.

From morning to night the wind howled at fifty, even sixty miles an hour. It was a constant screaming sound, rising at times to a shrill whistle. In such cold, even the simplest manual tasks required superhuman resolve.

Mackiernan's clothes had long since become tatters, which he, like the other men, repaired as best he could. But a bigger concern was how to protect their feet in the deep and frigid snowdrifts. After so many miles, the men had virtually walked out of the soles of their shoes. One day, Mackiernan and Zvonzov spotted two yaks. Both men were thinking shoes and meat. Mackiernan let Zvonzov, the better shot of the two, have the honors.

From three hundred yards, Zvonzov brought the beast down. Right through the heart. They scurried through the snow to the animal as it lay on its side. They swiftly cut away its hide for soles and began removing steaks. But having cleared one flank, they were unable to flip the creature over, and were forced to abandon it, only half consumed.

As March, then April wore on, Mackiernan and his men plotted a course for the Tibetan border. At each new campsite, Mackiernan took out his radio and wired headquarters of his progress. He requested that Washington contact the Tibetan government and ask the then sixteen-year-old Dalai Lama to arrange that he and his men be granted safe passage across the border and that they be given an escort once they exited China. Washington sent back a confirmation. Couriers from the Dalai Lama would alert the border guards at all crossing points so that Mackieman and his band would be welcomed.

By now, Mackiernan set a course by ancient cairns and stone outcroppings. Nomads had pointed the way through the major passes, bidding them to be on the lookout for piles of rocks that rose like pyramids. Beneath each mound were the remains of others who had died in this harsh land. The ground was frozen too solid to yield to a grave, and so the bodies were simply covered with rocks. In so bleak a land, devoid of roads or signs, each such grave became a reference point, named for the person who had died there. Mackiernan passed by the grave of Kalibet and later Kasbek, fascinated at the small measure of immortality granted them. Each death was both a confirmation that Mackiernan was headed in the right direction and a reminder of the risks inherent in such a landscape.

Thousands of miles away, in Washington, the landscape of the Cold War was taking shape. On April 25, 1950, President Truman signed one of the seminal documents of the decade, National Security Council Directive 68. The blueprint for the Cold War strategy, it called on the United States to step up its opposition to Communist expansion, to rearm itself and to make covert operations an integral part of that opposition. The policy of containment was now the undisputed security objective of the era. The CIA had its marching orders.

But for Mackiernan it was not grand geopolitical issues that concerned him, but the ferocity of mountain winds and biting cold. The border had proved more elusive than he had imagined. Finally, at 11:00 A.M. on April 29, 1950, as he scanned the horizon to the southeast with his binoculars, he caught sight of a tiny Tibetan encampment and knew that he had at long last reached the border. It had taken seven months to cross twelve hundred miles of desert and mountain. A moment earlier he had been weary beyond words, his thirty-seven-year old frame stooped with exhaustion. Now, suddenly, he felt renewed and exuberant.

Mackiernan and Bessac went ahead, leaving the others to tend the camels. In the harsh terrain it was an hour before the Tibetans caught sight of Mackiernan, who was now a quarter of a mile ahead of Bessac. He was waving a white flag. The Tibetans dispatched a girl to meet him. They grinned at each other, unable to find any words in common. The girl stuck out her tongue at Mackiernan, a friendly greeting in Tibet, then withdrew to a hilltop where she was met by a Tibetan who unlimbered a gun. Then the two Tibetans disappeared over the hillside. Mackiernan followed and observed a small group apparently reinforcing a makeshift fortification of rocks. Their guns appeared to be at the ready.

Mackiernan decided that it would be best to strike camp here, on the east side of a stream that meandered through the valley. He chose a place in sight of the Tibetans. There he built a small fire to show his peaceful intentions. He suspected that the Tibetans might be wary of his straggling caravan, fearing them to be Communists or bandits bent on rustling sheep. As Mackiernan, Zvonzov, and the other two Russians drove tent stakes into the hard ground, six more Tibetans on horseback appeared, approaching from the northwest.

Moments later shots rang out. Mackiernan and his men dropped to the ground for cover. Bullets were whizzing overhead. Zvonzov reached for the flap of the tent and ripped it free. He tied it to the end of his rifle as a white flag and waved it aloft. The gunfire stopped. No one had been hit. Mackiernan directed Bessac to approach the first group of Tibetans and offer them gifts of raisins, tobacco, and cloth. As Bessac approached, he held a white flag and was taken in by the Tibetans.

Mackiernan, meanwhile, was convinced he could persuade those who had fired on him that his party was not a threat. His plan was a simple one. He and the others would rise to their feet, hands held high above their heads. Slowly they would approach the Tibetans as a group. Zvonzov argued against the plan. He feared the Tibetans would simply open fire when they were most vulnerable. Mackiernan prevailed.

Slowly he and the three White Russians stood up, hands aloft. They walked in measured steps, closing the distance between their tent site and the Tibetans. As they walked, Zvonzov eyed a boulder to the right and resolved that if there was trouble he would dive for cover behind it.

Mackiernan was in the lead, gaining confidence as the Tibetans held their fire. His arms were raised. Behind him walked the two White Russians, Stephani and Leonid. Fewer than fifty yards now separated them from the Tibetan border guards. Just then two shots were fired. Mackiernan cried out, "Don't shoot!" A third shot echoed across the valley. Mackiernan, Stephani, and Leonid lay in the snow. Vassily ran for the boulder. The air was thin and he ripped his shirt open as if it might give his lungs more air. A bullet smashed into his left knee. He tumbled into the snow and crawled toward the tent, his mind fixed on the machine gun and ammo that were there.

Moments later Bessac appeared, his hands tied behind his back, a prisoner of the Tibetans. Vassily, too, was taken prisoner. The six guards looted the campsite, encircled Vassily, and forced him to the ground. They demanded that he kowtow to them. Vassily pleaded for his life. Not long after, Bessac and Vassily, now hobbling and putting his weight on a stick, approached the place where Mackiernan, Stephani, and Leonid had fallen.

The wind was whipping at sixty miles an hour, the snow a blinding swirl. A half hour had passed since the shooting. Mackiernan was lying on his back, his legs crossed. Vassily looked at Mackiernan and thought to himself how peaceful he looked. Mackiernan even appeared to be smiling. It was a slightly ironic smile. Vassily was overcome with the strangest sense of envy.

Just then one of the border guards began to rifle through Mackiernan's pockets. He withdrew a bursak, one of those biscuits Mackiernan was never without. He offered Vassily a piece. Vassily turned away in revulsion. Then the guard pressed the biscuit to Mackiernan's teeth. The mouth fell wide open. Vassily was overcome with nausea. He turned and walked away. Mackiernan's body was already stiffening. But there would be one more indignity Mackiernan and the others would endure. The guards decapitated Mackiernan, Stephani, and Leonid, and even one of the camels that had been felled by their volley.

Shortly thereafter, the guards realized that they had made a terrible mistake, that these men were neither Communists nor bandits. They unbound Bessac's hands and attempted to put him at ease. Then Bessac and Vassily, in the company of the guards, began what was to be the last tedious march, to Lhasa and to freedom.

Five days after Mackiernan was killed, the two surviving members of his party encountered the Dalai Lama's couriers who were to have delivered the message of safe conduct and who were to have been part of Mackiernan's welcoming party. The couriers gave no explanation or excuse for their tardiness. It was small comfort that they offered Bessac the opportunity to execute the leader of the offending border guards. It was an offer he declined.

Three days later, Tibetan soldiers made the arduous trip back to the border to retrieve that which had been looted -- including the remaining gold -- and to return the heads of Mackiernan, Leonid, and Stephani, that they might be buried with their bodies. The camel head was taken on to Lhasa. While convalescing, Vassily carved three simple wooden crosses to stand above the graves on the Tibetan frontier.

Mackiernan and the others were buried where they fell.The place was called Shigarhung Lung. There was no funeral for Mackiernan, then or ever. His grave was marked by Vassily's cross. It read simply "Douglas Mackiernan." He was buried beneath a pile of rocks, not unlike those many simple graves that he had paused to admire along the way and by which he had plotted his own course. Eleven days after the killing, the border guards who had killed him received forty to sixty lashes across the buttocks.

On June 11, 1950, Vassily and Bessac finally reached the outskirts of Lhasa. In the final entry in the log, Bessac wrote, "Good to be here -- Oh God."

-- The Book of Honor: The Secret Lives and Deaths of CIA Operatives, by Ted Gup

We Westerners have really been taken for a ride with this Tibet myth. We've literally been following the advice of savages.In the Tibetan army it is easy to recognise the difference between officers and men. The higher his rank the more gold decorations an officer wears. There seem to be no proper regulations about dress. I once saw a general who in addition to his gold epaulettes had a collection of glittering objects pinned on his breast. He had probably spent too much time looking at foreign illustrated papers and had decorated himself accordingly, for there are no Tibetan military medals. Instead of mentions and distinctions the Tibetan soldier receives more tangible rewards. After a victory he has a right to the booty, and so looting is the general rule. He is, however, obliged to deliver the weapons he has captured. A good example of the utility of this system can be found in the battles against the bandits. The local Ponpos are entitled to call on the Government for aid when they can no longer cope with the robbers. Small military detachments are then sent to help them. In spite of the ruthless manner in which the bandits fight, service in these commandos is very popular. The soldiers have their eye on the plunder and ignore the danger. The soldier’s right to the spoils of war has been the cause of a great deal of trouble. In a case with which I was personally connected, it cost the lives of several persons.

When the Chinese Communists occupied Turkestan, the American consul, Machiernan [Douglas Mackiernan], with a young American student named Bessac and three White Russians, fled to Tibet, having first requested the U.S.A. Embassy in India to ask the Tibetan Government for travel facilities. Messengers were sent from Lhasa in all directions to instruct the frontier posts and patrols to make no difficulties for the fugitives. The party travelled in a small caravan over the Kuen Lun mountains. Their camels stood the journey well, and they obtained fresh meat by shooting wild asses. By ill-luck the Government messenger was late in arriving at the spot where the party was to cross the frontier. Without challenging or finding out who was approaching them, the soldiers of the outpost, tempted by the sight of a dozen heavily laden camels, fired on the caravan, killing on the spot the American consul and two of the Russians. The third Russian was wounded and only Bessac escaped unhurt. He was taken prisoner and brought with the wounded man to the nearest District Governor. On the way the two men were insulted and threatened by the soldiers, who had first shared among themselves the spoils and had been overjoyed to find such valuable objects as field-glasses and cameras. Before they reached the next Ponpo the Government messenger came up with the escort, with orders to treat the Americans and their party as guests of the Government. This caused a change of attitude. The soldiers outdid one another in politeness: but the damage could not be undone. The Governor sent a report to Lhasa, and the authorities, horrified by the news, did their utmost to express their regret in every possible way. An Indian-trained hospital orderly w’as sent with presents to meet Bessac and his wounded companion. They were invited to come to Lhasa and asked to bear witness for the prosecution against the soldiers who had already been arrested. A high official who spoke a little English rode out to meet the approaching travellers. I attached myself to him thinking that it might be some comfort to the young American to have a white man to talk to. I also hoped to convince him that the Government could not be blamed for the incident, which it deeply regretted. We met the young man in pouring rain. He was as tall as a hop-pole and completely dwarfed his little Tibetan pony. I could well imagine how he felt. The little caravan had been months on the road, always in flight from enemies and exposed to dangers, and their first meeting with the people of the country in which they sought asylum brought three of their party to their deaths.

New clothes and shoes were waiting for them in a tent by the wayside and in Lhasa they were put up in a garden-house with a cook and a servant to look after them. Fortunately the Russian, Vassilieff, was not dangerously wounded and was soon able to hobble about the garden on crutches. They remained for a month in Lhasa, during which time I made friends with Bessac. He bore no grudge against the country which had at first received him so ill. He asked only that the soldiers who had ill-treated him on the way to the District Governor should be punished. He was requested to be present at the execution of the sentence, so as to make sure there was no deception. When he saw the floggings, he asked that the number of lashings should be reduced. He took photographs of the scene, which later appeared in Life as a testimonial to the correct attitude of the Tibetan Government. Everything was done to pay the last honours to the dead according to Western customs. So it is that three wooden crosses stand today over their graves in the Changthang. Bessac was received by the Dalai Lama and afterwards left for Sikkim, where he was met by fellow-countrymen.

The troubled times brought many fugitives to Tibet, but none were so unlucky as this party.

-- Seven Years in Tibet, by Heinrich Harrer

And these people would completely OWN Buddhism as a whole! We absolutely cannot let this happen.

One of the monk policemen, bearing his heavy staff.

The Monks' Dance at the foot of the Potala, during the New Year's festivities.

And I have not been able to find ANY precedent for lamas having harems of wives. There is no doubt in my mind that if Trungpa had tried this in Tibet, he would have been sewn into a yak skin and thrown over a cliff.

Re: The Way I See Trungpa Now

The Karmapa strongly disapproved of Trungpa's marriage to Diana, and essentially wrote him off as a legitimate lama when he did that. Did Karmapa have a wife? No! As Diana says, "He was very strict about his monastic vows."

Karmapa had expected Trungpa to keep his monastic vows, and not have a wife, much less WIVES!

So Trungpa simply took advantage of American women, pretending it was all according to "tantric" tradition, using our endless gullibility to exercise his misogynistic power.

Thank God for the "Me Too" movement, which teaches women to fight back. We women have got to stop being "nice" and aiding and covering up for men's abuse of women.

Typically, Trungpa is lying to Diana, explaining everything from the perspective of himself being a great lama, difficult to seduce. Diana, believing this silly dodge, is a useful idiot, just as she was when she followed Trungpa's order to lie to the Karmapa by telling him every impressive building in Boulder was owned by Vajradhatu. Diana is like a tube that Trungpa's lies pass through in every direction. Since she delivered herself to him as a "barely legal" teen, she has swallowed every deception he could deliver, and passed each one along like a pearl of wisdom. The true significance of the Karmapa's disapproval was not that Trungpa was a monolith of Dharma probity -- the Karmapa surely knew Trungpa had an affair with the nun someday-to-be-known as the "Lady Konchok" -- who could only be seduced by a serious demoness. Rather, the likely meaning of his frowning brows was simply that she was bad news, the sort of troublesome female who could get between the important male relationships in a man's life.His Holiness was very strict about his monastic vows ... While His Holiness was in Boulder, Rinpoche invited him to have tea at our home in Pine Brook Hills. While he was at the house, I noticed that the Karmapa wouldn't make eye contact with me. I felt badly about this, and later I asked Rinpoche why His Holiness wouldn't look at me. Rinpoche said, "He's very uncomfortable around you." And I said, "Why on earth would that be?" He said, "Because if you had the power to seduce me, you must be a very dangerous woman." After the first time he came to the house, Rinpoche talked with him about our marriage, and explained that I was not a seductress. Then, His Holiness seemed more comfortable around me, and in fact we had a very close, wonderful relationship. But that first encounter was very disconcerting.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

Karmapa had expected Trungpa to keep his monastic vows, and not have a wife, much less WIVES!

So Trungpa simply took advantage of American women, pretending it was all according to "tantric" tradition, using our endless gullibility to exercise his misogynistic power.

Thank God for the "Me Too" movement, which teaches women to fight back. We women have got to stop being "nice" and aiding and covering up for men's abuse of women.